‘When you don’t have the resources, you have to be distinct’: Tracksmith founder Matt Taylor

Tracksmith is quietly carving out a slice of the running market by focusing relentlessly on an area the global sportswear giants have overlooked: running culture. ‘When we started, I didn’t even want to show running,’ says Matt Taylor, the founder. ‘I thought we could show the before and after — the workout, sleeping, eating and everything surrounding it.’ Tracksmith’s strategy effectively reframes consumer criteria for choosing a running brand from the latest trends and technical performance (favoured by giants Nike and Adidas) to the brand that most understands running culture. And it’s working — the company has increased revenue by over 280% over the last two years, with expansion plans underway; a second store (after Boston) opens in London in Spring 2023, with a third in New York soon after. We speak to Matt Taylor about the ‘Running Class’ mindset, their unique innovation process and advice for brands needing to cut through the noise.

Matt Taylor, Tracksmith founder. Photo: Emily Maye

Why start Tracksmith? Why did the world need another running brand back in 2014?

A real driving force for me was wanting to elevate the way running was presented to the world. When I started the journey ten years ago, everything on the market looked the same — cheap materials, lack of style — if you removed the logos from the apparel, especially men’s apparel, you’d have a hard time distinguishing the brand as a consumer. So there was this opportunity to make higher quality and more functional products, but also a much more understated, less loud product. Lastly, I felt like there was a pretty big cultural void in running, where the brands that we all know and that have been around for a long time have drifted to each end of the spectrum. At one end, they’re hoping to align with Olympic Gold Medalists and world record holders, and at the other, they are hoping to convince a consumer to get off the couch and go for their first run. In the middle of that were millions of runners like myself that would never be professionals but were way beyond hobby joggers or beginners. We were committed to it. We identified as runners. It was a part of our lifestyle. Yet, no one was really speaking our language. So those things combined just felt like an opportunity to create something distinct from the market.

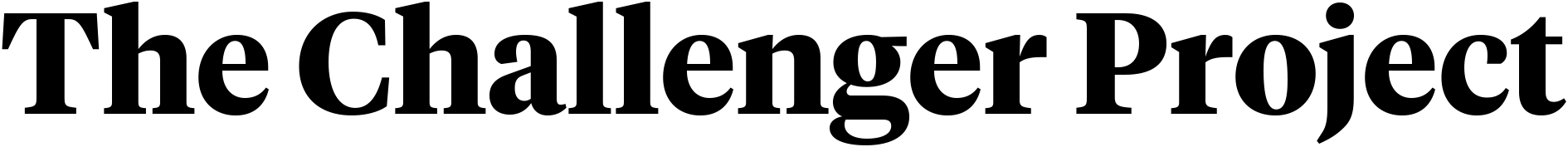

‘Champion for the running class’ banner at Tracksmith pop-up event in New York City in 2021.

That group in the middle is what you’ve dubbed the running class, correct?

Yeah, exactly. It’s not at all about how fast you are. It’s not about how many miles you run or whether you’ve run a marathon. We talk about it internally as a ‘committed runner.’ It’s much more about a psychographic; it’s when you have made that switch in your life that running will become an important part of your lifestyle. That may be every day. It may be every other day. It is when a consumer makes that shift to something that they become more passionate about.

How have you got the organization to buy into the company values or know what the Tracksmith way is when they have to make a decision?

To be honest, two or three years ago, I probably didn’t catch that quickly enough as we brought more people in. In the first year or two or three, everyone’s close to the brand’s origin story; you hear all the stories, and you know why this thing exists or why the logo looks like that. Over the last year, I’ve just doubled down to make sure that there is a process for new employees to understand the origin story and why things are how they are. It will sound like a simple idea, but it’s just consistency and repetition. We have regular team meetings, and these things are consistently stated. We provide an opportunity in an open forum to ask questions, to challenge something. By forcing those conversations, my goal is that, as the team grows from 50 to 100 to 500, we can continue to maintain those things that make the brand distinct and unique while also allowing new viewpoints and new experiences to come into the brand because you do need to evolve.

Tracksmith entered the footwear category in 2021 with its ‘Eliot Runner.’

Your products display a particular brand point of view that is really interesting. There are two different threads almost playing out in them. Some of them meet the needs of runners, so solving for specific situations. And some are more around running culture, whether pulling from history or everyday running moments like Cannonball Run. What’s your process for getting something from an idea to a finished product?

Our process is driven by narrative and concepts, and it starts with a cross-functional team. A lot of times, at bigger companies, the product team will hand something over to the marketing team that they weren’t involved in, or the marketing team will come up with a great concept, and they have to force a product into it that wasn’t conceived together. So although we don’t get it right every time, we try to start every season, every year, with a narrative and concepts that are agreed upon and aligned across the org so that when the product team goes and starts their work stream, and the marketing team starts theirs much later on in the process, because the timelines are just different, everyone is working around the same assumptions and not in silos.

That’s really interesting. I don’t think I’ve heard of many companies doing that in that unified of a way. It also sounds like it could be pretty tricky, though. I’m curious how you arrive at those themes that sit over both product and marketing. How do you filter those ideas down?

There are several inputs that various groups within the org come with. It could be consumer feedback. It could be market trends. It could be the performance of certain product categories or whatever. Everyone digests that. Then we go through a process we call the Golden Bubble. It’s just the way it was drawn on a chart one day. That is really just a grinder of ideation and creativity. We allow ourselves to have no boundaries at the beginning. Then, as we go through that process, we whittle that down into things that we start to feel good about and can see coming to life. Then there’s a rating process. We look at a couple different things. How hard is something to execute given our resources, supply chain partners, et cetera? How much impact could something have on the brand? Some products could have a huge impact from a buzz perspective but not be commercially that strong, while other products could be very commercially strong but not super interesting. So we just run it through our process. That’s roughly a month. We spit out what we then turn into product briefs for the product team to start their process. Different ideas and opinions exist, but when you filter through all of that, some things become clear.

Well, I think that idea of grading brand impact is one of the things that matters because I know a lot of companies would say, ‘What would the business impact of this be?’ — that’s, of course, part of it. But it sounds like some of it, too, would be, ‘Does this reinforce our brand?’ Is that right?

Yeah, that’s definitely right. We’ve lived through an era of performance marketing — perhaps we’re still in it, where it’s just all about the unit economics of your performance marketing spend, which can build a business, but it’s hard to build a brand. I always think brand investments are for your balance sheet, and performance marketing is for your P & L. You need to balance those things because, ultimately, over time, you still need a strong brand. It’s just making sure that you get that balance right. We coddle the brand. I admit that. We’re very careful of it and want to protect it.

I’ve heard you talk about how building a brand is like running — like how it’s a long game, and you get a little better each day. Are there other ways you feel that’s true?

A lot of brand building requires consistency. This idea that a consumer sees one thing and makes a decision happens, but it doesn’t happen all of the time. Often, we need multiple impressions, engagements, or interactions before we decide even to explore more, let alone make a purchase. So this idea that ‘Oh, I saw a banner ad, I clicked on it, and I bought it’ is pretty narrow. So having consistency over a long time, the dividends pay off on the consumer journey. Maybe you weren’t into running two years ago. Now you’re starting to get into it. A brand has been percolating. Then perhaps a catalogue drops in your mailbox. And so on. Consistency is really important. That said, as I mentioned earlier, brands also need new stimuli. You need to evolve. You can’t just do the same thing every day and expect to have constant improvements. Like running, you get the reward for putting in this block of training or this block of commitment and consistency in the business, or brand-building. Then you need to add on top of that. You optimize that part of your muscle memory and then look for new stimuli. It’s an evolving process. There’s no specific formula for it. You have to go with gut on like, ‘Okay. Yeah, we’re done. This is established. Now, what comes next.’

‘The Trackhouse’ in Boston is Tracksmith’s first retail store and a community hub for runners.

Are there any artefacts that help ensure that consistency? What sources of inspiration are you drawing from to get the right stability and avoid getting stale?

There’s no shortage of inputs out there. The nice thing, I guess, is that it sounds so cliché, but Tracksmith is for runners, by runners. We are living and breathing the culture and the community. We’re out there running, racing, training, and consuming the same media. So there’s a lot of those inputs. Then I think it’s just trying to filter those through. What makes sense for it from a business perspective? What makes sense from a product perspective? What makes sense from a brand perspective? Any idea can sound great for a while. Then you live with it for a bit and realize, ‘That probably doesn’t make sense for us.’ So it’s just a balance of finding those sources of inspiration and those elements and variables and ensuring they hold up over time.

To build on that, one bit of meaning that I’ve maybe read into is the calling back to the halcyon days of the amateur runner, and that being something that underpins and animates the entire brand. Is that an accurate connection?

No, that’s accurate. Boston, as our home, is the cultural hub. It’s the heart and soul of running because of the Boston Marathon, which goes back to 1897. It’s the oldest continuous foot race. There is this incredible collegiate and youth network in New England. Running in New England is almost just a part of life there. It’s hard to escape it. So that definitely drives a lot of how we think about that. We connect back to that time, but not just a specific era. We look at the history of running as a whole and its progress and evolution, and we draw a lot of inspiration from that.

Talking about Boston, I think a tangible manifestation of local running culture and what that means to the brand is ‘The Trackhouse’. Can you tell us some of the special things about that store?

The Trackhouse on Newbury Street was our first store. Our office is also above it. It’s about 400 meters from the finish line of the Boston Marathon. We’ve made some decisions that maybe we wouldn’t have made with a typical retail P & L analysis. We have a large space dedicated to community activities — we do a lot of runs from the store, workouts during the week, a long run on the weekends, we host yoga, and we have speakers come in. It’s not churning a lot of revenue per square foot because we have very little product up in that area. We’ve also recreated this famous runners’ bar called The Eliot Lounge, which was a Boston institution. It shut down in 1996. It was a bar all the athletes and sports writers went to, but it was run by runners. The bartender, Tommy Leonard, was the primary bartender – a very charismatic guy. All of his friends worked in the bar. It just has this legendary cultural status within running. We knew some people from the Boston area who used to frequent and work at the bar, including Tommy, so we recreated some of that upstairs. We got two of the original stools. Some elements like that pay homage to part of the cultural history of running in Boston. The original Eliot Lounge had this tradition where you would run the Boston Marathon, but then the real race was who would make it back to the lounge first. It was less than a mile from the finish line. So people would literally run the Boston Marathon, get through the finish line, ignore all the hype and hoopla and family and friends, and run back to The Eliot Lounge to try to be the first one there. So again, when that shut down, and we learned about that tradition, we brought it back to the Trackhouse in Boston. It’s a unique space for a retail store.

We’re also opening in London and New York. So London should open first and then Brooklyn shortly after that. London is two floors like Boston, which is great. We will have a similar area to the store, focusing more on community gatherings and events. We also picked the location, the street, and the neighborhood where we are, Marylebone in central London, because of the access to the parks. A huge part of our location scouting is like, ‘Where can we go for a run?’ Many people would assume a US brand coming to London would go to Soho or a place like that, but the running there’s just not great. We couldn’t envision being able to activate the community element of the brand as well there. The space where we are we’re a kilometer from Hyde Park and a kilometer from Regent’s Park. So we have a lot of access. It’s little elements like that, that make it unique.

Tracksmith’s ‘Church of the Long Run’ film follows runner Sam Roecker for 83-minutes in real time on her Sunday long run in Colorado.

Tracksmith obviously doesn’t have the media budgets of an established company. Yet you have this task of standing out amongst this really loud category. How do you think about marketing, given that? How do you cut through all that noise?

Do the opposite of what everyone else is doing. When you don’t have the resources, you have to be distinct. People are blown away when people realize how small our team is and what we’re able to produce on the content side. But that focus and having a sharp point of view on what we want to do and create allows us to do it. I would love more money for the distribution, getting it out there and spending it on placement, so people see it. But we know that when people see it, they have an emotional reaction, usually positive but sometimes negative. Frankly, that’s also good. On New Year’s Day, we released an 83-minute film of a woman doing a long run in Colorado. The goal was to do a single take, and we got close. There are no words. There’s just an ambient soundtrack to it. You’re just following this woman on this beautiful mountain road in the snow in the winter. It goes against everything that everyone would tell you for video. It should be short. It should be in vertical format. It should have a clear call to action. It was none of that. But when you see the reactions and comments, they are overwhelmingly positive. It connected with people deeply and brought back memories and emotions, and nostalgia and motivated people to want to get out the door. When we can do that and do it well, it can profoundly impact someone. At the same time, some people are like, ‘This is ridiculous. Who’s going to watch 83 minutes?’ But it’s good to have some people that hate what you’re doing, as well as people that love you. If everything were for everyone, it would be a boring world. So it’s nice to have a bit of tension there.

You talked about being almost different on purpose to break through the noise. In terms of content, it feels like it means showing these really quiet, human moments about running culture, instead of just performance. Is that difference by design?

Yeah. That was the hypothesis from the very beginning. Actually, to the point when we were starting, I didn’t even want to show running. I thought we could show the before and after, and a runner would recognize those moments in a way that they would connect with. But ultimately, people want to see the product in action, how it fits, and how it moves. So we had to shoot running as well, but we didn’t move away from documenting the lifestyle of this committed runner. So yes, that involves the hard run, the easy run, and the track workout, but it also involves sleeping, journal writing, eating, and all the other things surrounding it. Our photographer Emily Maye is incredible. She has a very documentary approach to her style, which has allowed us to create this visual breath for the brand that is unique in the running category.

You’re drawing from the history of the sport, but you’re also trying to write a better future as well, with initiatives like the Amateur Support Program and The Foundation, which aims to increase broader participation in track and field. Why are those acts so important?

The way we think about it internally is we want to drive running culture. We want to be amongst the people, brands, and events that are moving the culture forward. So we spend as much time or more thinking about that than we do thinking about inspiration from the past. Whether that’s something like The Foundation or The Fellowship, those are just manifestations of continuing to want to push running forward. In reality, it is a little experimentation when you are thinking about the future. You try things that are new and different and learn from them. Some will stick and be great, and some won’t, and that’s fine. That’s how it should be. Those are examples of ways we’re looking to continue to evolve and progress the sport for the future.

Enjoy this? Sign up for The Challenger Project newsletter from eatbigfish, and we’ll send you our monthly email with our very latest insight, interviews and case studies.

All images courtesy of Tracksmith