70 years of Swedish challenger brands

From Ikea to Absolut to Polestar, for a relatively small European nation (population of 10 million), Sweden has had an outsized impact on the world of challenger brands. But why has it been such fertile ground? And what can we learn from Swedish challengers today? We spoke to Niclas Norström, strategist at M&C Saatchi Stockholm and Swedish challenger enthusiast, to better understand Sweden’s history of building successful challengers.

Hej Niclas, tell us about the history of challenger brands in Sweden and how you think they’ve evolved over time.

Sweden’s global challenger brands cluster in four different waves. In the 1940s, Ikea and H&M democratised fashionable designs for the masses. They pioneered an operating model of making affordable products based on the latest trends that could very quickly get to market and managed to scale globally by entering markets when they reached a certain maturity. These early democratiser brands mirrored what in Sweden we call ‘Folkhemmet’ — a view that everyone in society should have access to a better life.

Absolut Vodka’s debut campaign ‘Perfection’ ran for 15 years and spawned 1500 variations, including collaborations with Andy Warhol and Keith Haring (above).

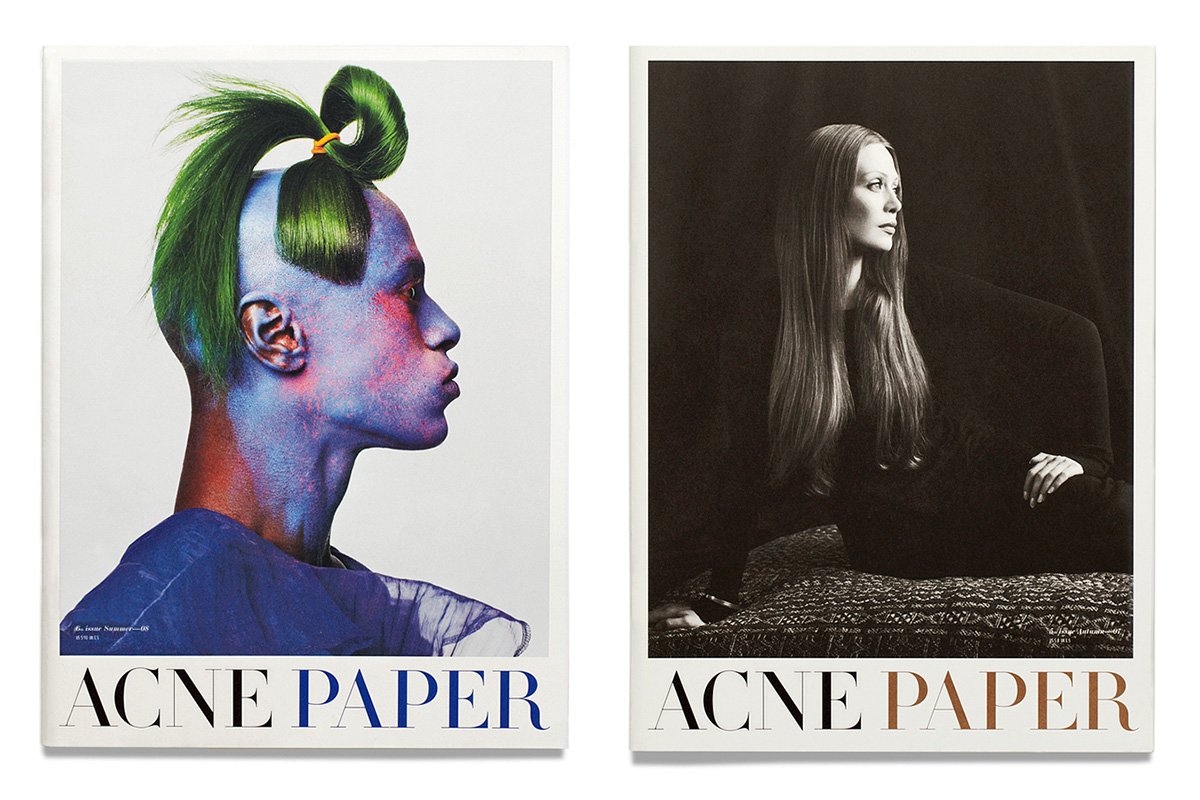

Then in the 1980s, Absolut launched in the United States and injected art, creativity and collaboration into advertising and communication. And we had Acne Studios, which started life as a creative agency but, after making 100 pairs of jeans as a direct mail to get some business, established a clothing business as well. It’s probably the only agency that’s managed to spin off and create a luxury global fashion house and brand.

In the last twenty years, digital disruptor brands like Spotify, Minecraft and Klarna have been content and entertainment-driven. These brands are less about advertising or ‘challenging’ something and more about being really good at building global platforms and hitting the right timing. These brands quickly reached over 100 million users.

And then, since 2010, we’ve had a new wave of Swedish challenger brands like Polestar, Northvolt and Oatly [relaunched 2014] that are much more product and design-centred and appeal to conscious consumers. It’s a simplification, but it feels like four distinct clusters of challenger brands.

Launched in 2005, Acne Paper was a magazine that explored photography, art, and literature and was an early form of content marketing for Acne Studios.

What was the context for each of these waves? What led to the birth of Ikea as a democratiser, for instance?

In Sweden, there’s a view that everyone in society should have access to a better life. And in my opinion, Ikea and H&M mirror that view of society by mixing good design with low prices. Then the pre-internet pop culture of the 80s and 90s was such a rich creative era for music, art and fashion, and I think that had a huge influence on brands like Absolut and Acne.

And then, around the dot com boom, Sweden heavily invested in home computing and broadband infrastructure. In the 1990s, it was government policy to put a PC in every home. I think the government thought it would pay off 10-20 years later. It opened up possibilities because we had fast and stable network connections from the beginning, which made it possible to enter online gaming and e-commerce early compared to other markets.

And I think the fourth wave impact brands like Polestar and Northvolt are about building amazing products that enable people to live more sustainably. They don’t talk about purpose. It’s not like Hellman’s mayonnaise, creating a purpose to do some purposeful advertising. It’s about less talk and more action. And I think it again connects to a long-held view of society here in Sweden.

Each new generation of challengers builds on the previous wave, and this context could open up new possibilities for brands. It might be that Sweden is quite early on the curve, especially regarding building global platform brands and appealing to more conscious consumers.

Looking at today’s Swedish challengers like Northvolt, Oatly and Polestar, what are they doing differently that’s enabling their progress?

Oatly’s ‘Ditch Milk’ OOH campaign in Shoreditch. Photo: Oatly.

I think they’re creative companies. Some of them have great ads and communication, but I think, for the most part, they’re unleashing creativity in all different aspects and areas of the company. In Sweden, we often have a relatively flat and open organisational structure and a lot of consensus thinking which might lead us more towards collaboration than in other parts of the world. And these companies are really strong at the intersection of design, engineering, innovation, and brand.

I also think there’s maybe a different kind of leadership. Their CEOs are not from traditional sales or finance backgrounds. Thomas Ingenlath, the CEO at Polestar, was Chief of Design at Volvo. Stefan Ytterborn, the CEO of Cake, also has a design background. And at Oatly, there is a strong connection or collaboration between their CEO Toni Petersson and their creative lead. They don’t have a marketing department but the ‘Department of mind control’ that can be anywhere in the company. And at Houdini Sportswear, again, it’s a strong partnership between the head of design and the CEO.

All these brands overcommit to design and are uncompromising regarding their design principles. And the leadership are really aware of the potential and power of design and design thinking to create unique brands and fuel growth. It doesn’t have to be product design, like Oatly; it could be the packaging design with that potential. I’ve always believed in this setup since Domenico de Sole and Tom Ford turned the Gucci brand around in the 1990s. It’s the creative side, understanding the business part and the business side — the CEO, understanding the creative side, and they run together in parallel, and I think that’s really interesting when it works.